Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) is a project of the Climate Council. We are 100% independent and funded by donations from people like you. Your donation will ensure our vital work continues.

When cities burn: Could the Los Angeles fires happen here?

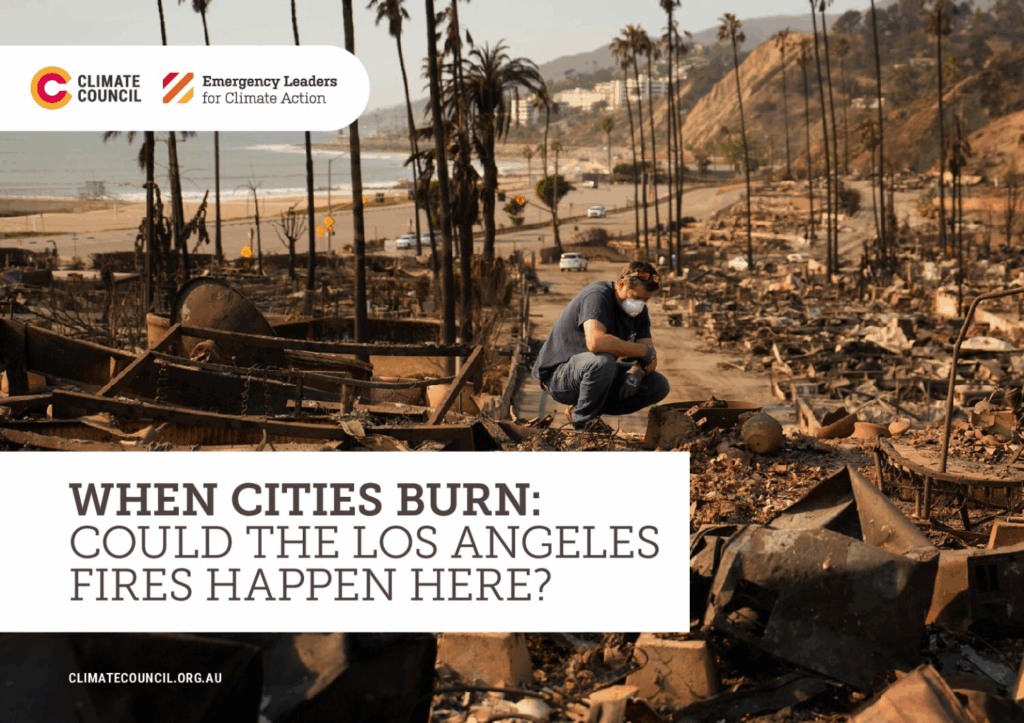

In January 2025, in the middle of the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, Los Angeles was overrun by a firestorm that killed 31 people, destroyed more than 16,000 structures, and left one of the world’s best-resourced firefighting teams overwhelmed. This prompted an immediate, and unsettling question for many Australians: could something like this happen here?

Our new analysis brings together the latest science, climate trends and fire behaviour research to provide the answer.

The uncomfortable truth is that many of the factors that led to the LA disaster are already present in Australia — and getting worse. Climate pollution from burning coal, oil and gas is supercharging heat, drying out landscapes, lengthening fire seasons and fuelling more extreme fire weather across fire-prone regions.

Australians have already experienced fires with the same hallmarks of the LA fires: drought- parched forests, strong winds, low humidity, explosive fire behaviour, and unstoppable fire fronts that fire agencies, no matter how well-resourced, struggle to respond to.

In 2003, it happened in Canberra. In 2009, Black Saturday hit Victoria. Tasmania and the NSW Blue Mountains were ablaze in 2013. Then, the national megafires of 2019-20: the Black Summer bushfires; the most destructive and widespread in Australia on record.

What Australia has not yet experienced — but is increasingly at risk of — is what Los Angeles endured: a major fire hitting a major city.

Our latest analysis explains that millions more Australians now live on the expanding outskirts of our capital cities and major regional centres, where homes adjoin highly flammable bush and grasslands.

These at-risk communities — from the Dandenong Ranges in Victoria, Perth Hills, Adelaide Hills, the Blue Mountains, Sydney suburbs, NSW Central Coast, Hobart’s suburbs and Canberra’s western edge — are already some of the most fire-exposed urban areas in the world.

In this report, we outline how climate change played an instrumental role in supercharging the main factors that underpinned the Californian catastrophe, and compare those conditions across Australia’s capital cities. We also explain why firefighters are increasingly facing fires they cannot stop; and what must be done to protect Australian lives, homes and communities as extreme fire weather intensifies.

We still have a choice on just how dangerous future fire conditions become. Now is the time to reduce climate pollution further and faster, to adapt our cities, and prepare our fire services and communities for a future increasingly at risk of devastating bushfires.

Key findings

1. The shocking 2025 wildfires that ripped through Los Angeles neighbourhoods in the middle of winter were supercharged by climate pollution.

- Climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas shaped the dangerous and extreme weather conditions that drove these fires: record dryness; non arrival of the typical annual wet season; and hurricane-like winds gusting up to 160 kmh.

- Climate pollution has all but erased traditional fire seasons and turned them into an all-year-round threat. The January 2025 fires hit in the middle of winter, well outside of the traditional fire season from June to November.

- LA experienced climate whiplash: a rapid switch between two very wet years that resulted in extreme fire fuel loads, followed by very dry conditions ideal for fires.

- Around the world, climate pollution is driving worsening fire conditions: 43% of the 200 most damaging fires have occurred in just the past decade.

2. Many Australian cities share dangerous characteristics that made the LA fires so destructive, and many of our worst bushfires have also exhibited unstoppable fire behaviour.

- Like California, many parts of Australia have a hot and dry climate. Research shows between 2000 and 2023 the intensity and frequency of the worst fires in southern Australia and western North America rose sharply under more extreme weather conditions.

- Australia has suffered through fires with the same characteristics as LA: extremely strong winds, drought conditions, high fuel loads and unstoppable fire behaviour. During Black Saturday 2009 in Victoria, the fire danger index exceeded 200 (with 100 the upper limit of recognised fire danger rating up until 2009).

- Fire-generated thunderstorms, or pyroconvective events, were relatively rare with 60 such events recorded in Australia in the 40 years up to 2018. During Black Summer, there were at least 45 fire- generated thunderstorms.

- Our analysis shows that the outskirts of Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Adelaide, Perth and Hobart share characteristics that made the LA fires so destructive.

3. Just like in LA, more people than ever are living in harm’s way on the fast-growing urban fringes of Australian cities.

- In LA, hurricane-like Santa Ana winds (up to 160 km/h) created a firestorm that fed on tinder dry brush, then houses. From 1990-2020, 45% of all new homes in California were built where suburbs meet flammable terrain.

- Over the past 20 years, outer suburban populations have exploded in Australia, too: More than doubling in Melbourne and Perth, up 36% in Adelaide, 33% in Hobart and 24% in Sydney.

- More than 6.9 million Australians now live where suburbs meet the bush — the zones most exposed to deadly fires. Had the Black Summer bushfires directly impacted the edges of our cities or major regional centres – such as Sydney, Newcastle, Wollongong, the NSW Central Coast, the Dandenong ranges, the Adelaide Hills, the Perth Hills or Hobart – then property losses on the scale of LA could have occurred.

- Many of the LA homes that burnt were built before fire resilient building standards were introduced there in 2008. Up to 90% of Australian homes in high-risk fire zones were also built before modern bushfire standards existed — making ignition due to ember attack and house-to-house fire spread far more likely.

- Research shows that, globally, 10% of all fires result in 78% of all fatalities. Most of these occur in suburbs built where bush or grassland meets cities.

4. Climate pollution is turbo-charging Australian fire conditions, and it’s making fires more frequent, costly, intense – and less predictable.

- Since 2020 insurance premiums have increased by 78% to 138% for homes in bushfire-prone Local Government Areas within Sydney, Melbourne and Perth.

- The cost of the 2019/20 Black Summer bushfires to our economy was estimated at $10 billion. It is a matter of when – not if – we’ll experience another fire on this scale, or worse, as dangerous fire weather conditions driven by climate pollution make this a near certainty.

- From 1979 to 2019 fire seasons across Australia grew by an additional 27 days – a 20% increase over the 40-year period.

- Southern Australia is experiencing long-term declines in cool-season rainfall at the same time as spring and summer become hotter and drier: setting the stage for earlier, more intense and widespread fires like the 2003 Canberra fires and 2009 Black Saturday bushfires.

- Fire behaviour at night is becoming more extreme and robbing firefighters of a tool they’ve used for centuries: attacking fires and backburning during milder night conditions to bring large fires under control.

- The world’s first large-scale fire-generated tornado – and the fastest rate of spread for a forest fire – was recorded in Canberra, in January 2003.

5. Climate-fuelled fires are increasingly exceeding the limits of modern firefighting. Investment in community preparation and urgent cuts to climate pollution are both critical to saving Australian lives and communities.

- There is no way to safely or effectively fight pyroconvective events, like those experienced in Canberra 2003, Black Saturday 2009, and the Black Summer bushfires. Aircraft must be grounded, and efforts to protect properties temporarily abandoned.

- Modelling shows that 3°C of global warming would result in catastrophic fire danger zones three times bigger than experienced on Black Saturday in 2009 (810,000 km2) with temperatures as high as 48°C in Victoria, NSW, and South Australia.

- Fires on this scale are considered beyond the limits of any fire service to control. Los Angeles is one of the best-resourced firefighting jurisdictions in the world, but was still overwhelmed: extreme winds grounded aircraft, simultaneous fires limited assistance, and there was sudden loss of water pressure.

- Australia is facing more days of extreme fire weather and larger, more damaging fires under worsening fire weather caused by climate pollution. We must:

- Cut climate pollution from coal, oil and gas more swiftly and deeply if we’re to avoid even worse.

- Invest heavily in disaster preparation and community resilience at all levels of government so we’re as prepared as possible for the worsening fire risks we already face.

- As a priority, increase emergency service and land management capacity at the urban fringe of our cities and major regional centres so growing populations are better protected for what’s to come.

For media enquiries or interviews with ELCA members

Contact Media Manager, Jacqui Street

0498 188 528 / jacqui.street@climatecouncil.org.au